Feminist placards: the language of protest

You may have heard that “well behaved women seldom make history”. This popularised phrase actually comes from the Pulitzer-prize winning Laurel Thatcher Ulrich. Taken out of context, you may think it’s a call to behave badly. Ulrich meant it differently. She is a historian. She wanted to discuss how “well-behaved women” haven’t been written into history. Their lives have been largely domestic.

She wants people to understand that it isn’t merely the stereotyped feminist who can shake things up. Ordinary people, too, can do something unexpected and make history.

Banners have a way of bringing together feminists from all walks of life. Something we should celebrate when the intersectionality of feminism is under threat.

The so-called “well-behaved” and “badly-behaved” can both get their message out there. Concisely and powerfully. We’ll look at a handful of these and examine the power of their language.

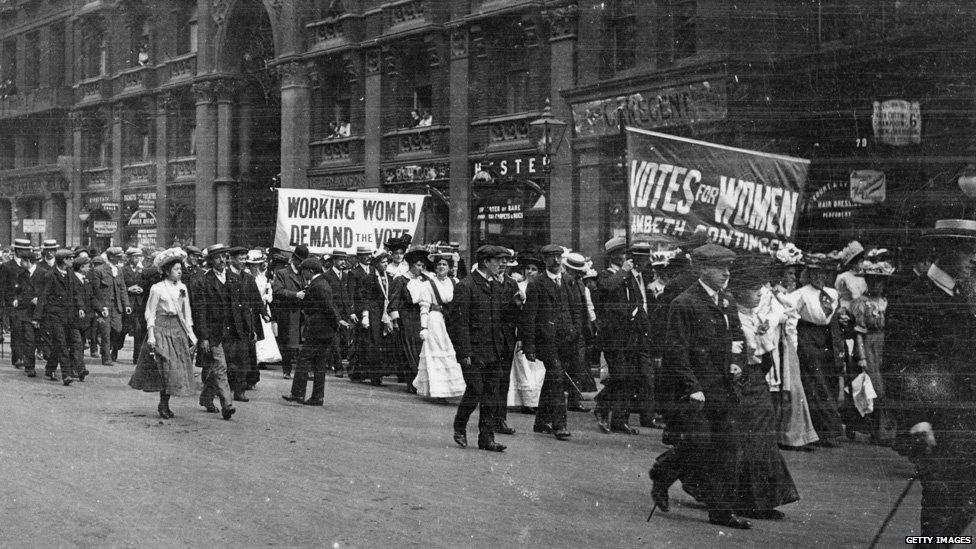

“Working women demand the vote”

These banners are from around 1900. Many slogans at the time were short and simple. Most of them simply said “votes for women”. It’s easy to take this for granted now. But, it’s important to kick this off with where it all began.

Feminism existed before the suffrage movement. You may know of protofeminist writers such as Mary Wollstonecraft. But, women owe many rights to these brave suffragettes and suffragists of the 20th century.

The most impactful word on this placard is ‘demand’. The etymology of the word reveals:

‘Meaning “ask for with insistence or urgency” is from early 15c., from Anglo-French legal use (“to ask for as a right”).’

It goes without saying now that women have the right to vote, but this is what they were fighting for in the early 1900s. They’ve harnessed the sexist stereotype of the demanding woman and taken ownership of it. You may remember the #banbossy campaign of 2014 in which Beyoncé stated, “I’m not bossy. I’m the boss.” These women are saying, “I’m not demanding. I demand this human right.”

“Welcome to the Miss America cattle auction”

This photo was taken at a Miss America protest in 1968. 400 women protested against America’s beauty expectations at the time. They even continued the livestock theme by crowning a live sheep.

This protest is where a certain myth came from. You must have heard of “bra burning”. They had a “freedom trash can” at the protest. In it, they disposed of feminine objects.

The media latched on to this. In fact, they were going to burn the trash can. But, the police halted their efforts.

Regardless of this, the language in their placard paired with the powerful imagery they used burned this event into feminist history.

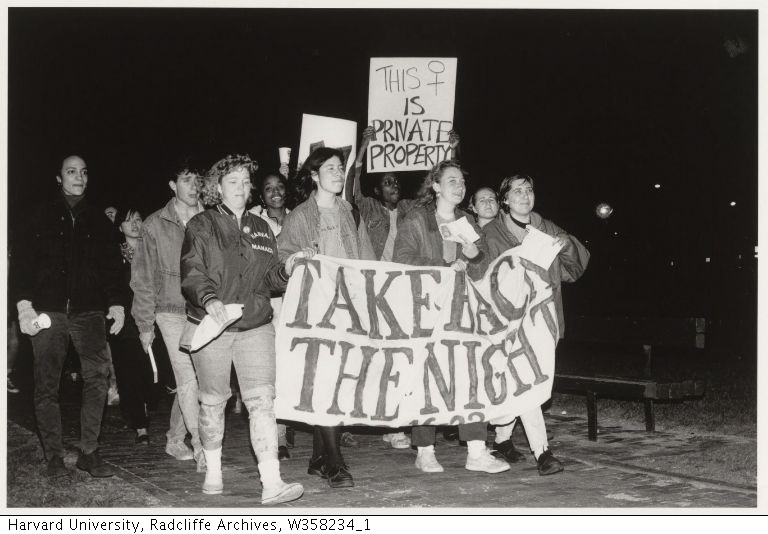

“Take back the night”

Taken in 1980, this photo depicts students taking part in a Take Back the Night protest. These were popularised across university campuses. They started formally in the 1970s and continue today.

The simple but effective “take back” term reminds us that the night feels taken away from women. That many live their lives in fear of assault. If you’re a woman, chances are you have feared the night in your life. The walk is a worldwide effort to combat sexual violence and violence against women.

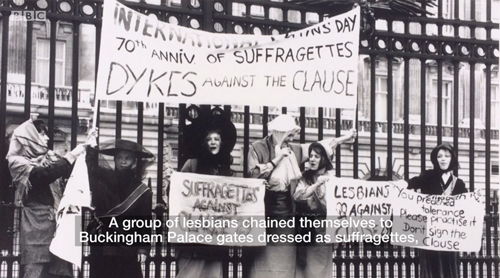

“Dykes against the clause”

Source: BBC

Returning to the suffragettes, this is our next banner of choice. It comes from a group of British lesbians dressed as them. They were chained to the Buckingham Palace gates in the late 1980s. If you weren’t there, the “clause” they refer to is Section 28 of 1988. This ‘stated that a local authority ‘shall not intentionally promote homosexuality or publish material with the intention of promoting homosexuality’. (Wikipedia). During this time, 75% of people when surveyed said it was wrong to be gay.

It’s important to document this in feminist history. In the late ‘80s and ‘90s there was a feminist push to recognise lesbians. This resulted in the changing of the ‘GLBT’ acronym to ‘LGBT’.

This photo is the perfect illustration of the solidarity reinforced between gay men and lesbian women during the 1980s. Their support of gay men during the AIDS crisis was extraordinary. It is a good reminder that feminist concerns are inextricably linked to other oppressed groups.

We can see a variety of styles on these banners. One pleads, ‘You preached tolerance. Please practise it. Don’t sign the clause’. However, it doesn’t have the commanding power of ‘Dykes against the clause’. Although it doesn’t use the imperative ‘don’t sign’, it makes a clearer stance with the word ‘against’, being unambiguously in opposition to the clause.

“I stand for justice for trans people”

Source: Smithsonian

This 2015 photo is part of a curation on black feminisms. It is pluralised to emphasise the need to be truly intersectional. To address all lived experiences, cultures and worldviews.

It highlights the need to recognise black women, particularly queer black women, in feminist history. Similarly to the earlier LGBTQ+ example, this slogan illustrates the strong connection between feminism, queer rights, and intersectionality.

Interestingly, there are two banners with the same message, but phrased differently. One says simply, ‘I stand for / trans / justice’. Another says, ‘I stand for / justice for / trans people’. Although slightly longer than the former, the repetition of the word ‘for’ arguably makes it more effective. Also impactful is the use of the word ‘people’. It reminds us that trans rights are human rights.

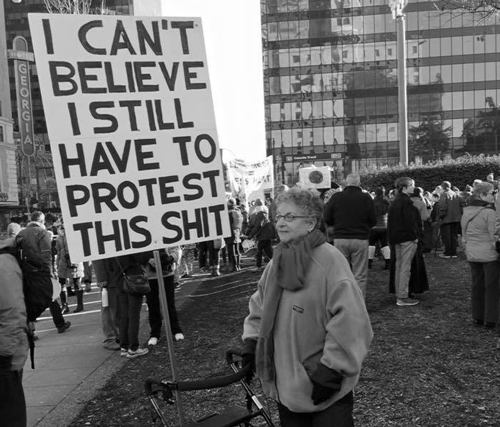

“I can’t believe I still have to protest this shit”

To end on a positive note, we have this fantastic example from 2016. The anonymous woman has her placard firmly secured to her Zimmer frame. After all these years, she knows as well as you do that there’s still a long way to go.

The operative word on her placard is ‘still’. It isn’t emphasised by underlining or italicizing and visually is weighted equally with the other words. But, it sticks out as the most important. It’s a deceptively simple word, but it is vital to the message. In one sense she’s ‘still’ protesting this shit. In another sense, she refuses to be ‘still’.

She’s still out there protesting by the younger generation’s side. Inspiring a deluge of similar placards, she gives a clear message. You don’t let women’s rights regress. You keep moving forward. And you don’t give up.