10 English words with surprising etymology

“Every word carries a secret inside itself; it’s called etymology. It is the DNA of a word.”

— Mary Ruefle, Madness, Rack & Honey

“Etymology” derives from the Greek word etumos, meaning “true.” The practice of etymology is uncovering the truth by tracing the root of a word. If you’re interested in language, it can be quite exhilarating. Like being a linguistic detective.

The English language is strange at the best of times, it being a historical cocktail of Germanic and Latinate influences. Never is this more apparent than when we trace the origins of words. We used the fantastic resource etymonline for all the definitions and origins cited in this article.

1 | Disaster

disaster (n.)

- “anything that befalls of ruinous or distressing nature; any unfortunate event,” especially a sudden or great misfortune, 1590s,

- from French désastre (1560s),

- from Italian disastro, literally “ill-starred,” from dis-, here merely pejorative, equivalent to English mis- “ill” (see dis-) + astro “star, planet,”

- from Latin astrum,

- from Greek astron “star” (from PIE root *ster- (2) “star”).

The origin of the word points to unfavourable events being blamed on certain planet positions. Destiny is written in the stars – in some conceptions of fate in mythology, the universe is fixed and inevitable.

2 | Muscle

A far cry from World’s Strongest Man, the origin of the word ‘muscle’ is perhaps the most surprising.

muscle (n.)

- “contractible animal tissue consisting of bundles of fibers,”

- late 14c., “a muscle of the body,”

- from Latin musculus “a muscle,” literally “a little mouse,”

- diminutive of mus “mouse” (see mouse (n.)).

Rather than relating to strength and brawn as we understand it, ‘muscle’ is derived from the appearance of a muscle under the skin. Particularly biceps, which were thought both in Latin and in Greek to resemble a mouse running beneath the skin.

3 | Nice

Perhaps you’ve been told by an English teacher in the past to avoid using the word ‘nice’. This is because the word is so commonly used in our language that it’s not highly descriptive or imaginative.

Many English teachers consider it a cop-out. One of the most scathing commentaries on the word ‘nice’ is in Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey. Henry snarkily berates Catherine for overusing the word, remarking, “it does for everything.”

Yet its origins are far more interesting than the word appears.

nice (adj.)

- late 13c., “foolish, ignorant, frivolous, senseless,”

- from Old French nice (12c.) “careless, clumsy; weak; poor, needy; simple, stupid, silly, foolish,”

- from Latin nescius “ignorant, unaware,” literally “not-knowing,”

- from ne- “not” (from PIE root *ne- “not”) + stem of scire “to know” (see science).

- “The sense development has been extraordinary, even for an adj.” [Weekley] — from “timid, faint-hearted” (pre-1300); to “fussy, fastidious” (late 14c.); to “dainty, delicate” (c. 1400); to “precise, careful” (1500s, preserved in such terms as a nice distinction and nice and early); to “agreeable, delightful” (1769); to “kind, thoughtful” (1830).

Here, you can clearly see the amelioration of ‘nice’ throughout history. Interestingly, though, there are still hints of its root in how many people regard the word today. Although it came to acquire a positive meaning, we might associate it with the word ‘frivolous’ just as it was in the late 13th century. It is the kind of weak adjective many of us carelessly throw around, in want of a better word. With that being said, society undervalues niceness. It’s still nice to be nice.

4 | Cloud

cloud (n.)

- Old English clud “mass of rock, hill,” related to clod.

- The modern sense “rain-cloud, mass of evaporated water visible and suspended in the sky” is a metaphoric extension that begins to appear c. 1300 in southern texts, based on the similarity of cumulus clouds and rock masses.

- The usual Old English word for “cloud” was weolcan (see welkin).

- In Middle English, skie also originally meant “cloud.”

- The last entry for cloud in the original rock mass sense in Middle English Compendium is from c. 1475.

The origins of the word ‘cloud’ are surprising. You wouldn’t automatically associate their wispy appearance with the solidity of rocks. The etymology explains that it refers to the mass it accumulates and thus appearing similar to earth formations.

5 | Oxymoron

This is a great example of the word being an example of itself.

oxymoron (n.)

- in rhetoric, “a figure conjoining words or terms apparently contradictory so as to give point to the statement or expression,”

- 1650s, from Greek oxymōron, noun use of neuter of oxymōros (adj.) “pointedly foolish,”

- from oxys “sharp, pointed” (from PIE root *ak- “be sharp, rise (out) to a point, pierce”) + mōros “stupid” (see moron).

Now, it’s used more broadly to denote a contradiction in terms. Originally, though, it was a clash of terms around sharpness and dullness.

6 | Quarantine

Sorry to use this example mid-pandemic, but the origins of ‘quarantine’ may interest you.

quarantine (n.)

- 1660s, “period a ship suspected of carrying disease is kept in isolation,”

- from Italian quaranta giorni, literally “space of forty days,”

- from quaranta “forty,” from Latin quadraginta “forty,” which is related to quattuor “four” (from PIE root *kwetwer- “four”). So called from the Venetian policy (first enforced in 1377) of keeping ships from plague-stricken countries waiting off its port for 40 days to assure that no latent cases were aboard. Also see lazaretto.

- The extended sense of “any period of forced isolation” is from the 1670s.

- Earlier in English the word meant “period of 40 days in which a widow has the right to remain in her dead husband’s house” (1520s), and, as quarentyne (15c.), “desert in which Christ fasted for 40 days,” from Latin quadraginta “forty.”

We understand ‘quarantine’ as a period of isolation to prevent the spread of an illness, but the background on this is very interesting. The root of the word is more specific in the period of time elapsed.

7 | Tragedy

Without the word ‘tragedy’, we wouldn’t have one of the greatest songs by the Bee Gees. But there is also an interesting word history to be grateful for.

tragedy (n.)

- late 14c., “play or other serious literary work with an unhappy ending,”

- from Old French tragedie (14c.), from Latin tragedia “a tragedy,”

- from Greek tragodia “a dramatic poem or play in formal language and having an unhappy resolution,”

- apparently literally “goat song,” from tragos “goat, buck” + ōidē “song” (see ode), probably on model of rhapsodos (see rhapsody).

Although the specificity of the goat connection is debated, the connection to goats, in general, is accepted. There are a few different possibilities as to why. The etymology includes the literal translation “goat song”. Tragedy as we know it has its roots in ancient Greece, where it’s thought people dressed as goats and satyrs in plays. There are other theories surrounding goat sacrifices. Either way, who knew goats were involved at all?

8 | Surprise

What would a list of surprising etymology be without the word ‘surprise’ itself?

surprise (n.)

- also formerly surprize, late 14c.,

- “unexpected attack or capture,” from Old French surprise “a taking unawares” (13c.),

- from noun use of past participle of Old French sorprendre “to overtake, seize, invade” (12c.),

- from sur- “over” (see sur- (1)) + prendre “to take,” from Latin prendere, contracted from prehendere “to grasp, seize” (from prae- “before,” see pre-, + -hendere, from PIE root *ghend- “to seize, take”).

- Meaning “something unexpected” first recorded 1590s, that of “feeling of astonishment caused by something unexpected” is c. 1600.

- Meaning “fancy dish” is attested from 1708.

When you think of the word ‘surprise’ today, you might think of smiling faces. They’re shouting the word at you as you open your eyes to an unexpected party. Remember parties?

In history, though, it had a much more violent origin. The word is rooted in an invasion. In having the element of surprise as an advantage. It is also interesting that it has root words meaning “grasp”. This can also be related to words like “comprehend”.

9 | Comrade

It is interesting how the word ‘comrade’ is considered a non-neutral term. Whether it’s a veteran recalling time spent with his old army comrades, or used among the political left. Its origins point to it being more widely applicable.

comrade (n.)

- 1590s, “one who shares the same room,” hence “a close companion,”

- from French camarade (16c.),

- from Spanish camarada “chamber mate,”

- or Italian camerata “a partner,”

- from Latin camera “vaulted room, chamber” (see camera).

- In Spanish, a collective noun referring to one’s company.

- In 17c., sometimes jocularly misspelled comrogue.

- Used from 1884 by socialists and communists as a prefix to a surname to avoid “Mister” and other such titles.

- Also related: Comradely; comradeship.

With this considered, you could call any of your cohabitants “comrade”. And it’s perfectly acceptable to use it for your partner, no matter what your politics are.

10 | Clue

To end where we started, with the spirit of investigation, let’s have a look at the word ‘clue’.

clue (n.)

- “anything that guides or directs in an intricate case,” 1590s, a special use of a revised spelling of clew “a ball of thread or yarn” (q.v.).

- The word, which is native Germanic, in Middle English was clewe, also cleue; some words borrowed from Old French in -ue, -eu also were spelled -ew in Middle English, such as blew, imbew, but these later were reformed to -ue, and this process was extended to native words (hue, true, clue) which had ended in a vowel and -w.

- The spelling clue is first attested mid-15c.

- The sense shift is originally in reference to the clew of thread given by Ariadne to Theseus to use as a guide out of the Labyrinth in Greek mythology. The purely figurative sense of “that which points the way,” without regard to labyrinths, is from 1620s.

- As something which a bewildered person does not have, by 1948.

The word origins rooted in old stories like this are the most fascinating. A clue could be any object now. But, once upon a time, it was explicitly a ball of yarn a character used to find his way.

We always advocate being mindful of the language you’re using. Hopefully, you found it interesting to go on this etymological journey with us to uncover the truths of some words we take for granted.

Words of advice from the most successful authors

One of the most common questions people get in interviews is, “Who would you have a dinner party with, dead or alive?” We ask people this question because we want to know who they admire. Who they’d want to have a conversation with and take advice from.

The great thing about the written word is that it’s etched into history. Some of the greatest authors are sadly no longer with us, but their words live on. And some people have been lucky enough to speak to them about art, writing, and life.

Whether you’re a copywriter or you write fiction, nonfiction or poetry, you can take some lessons from these pieces of sage advice. We’ve looked at some bestselling authors and are sharing their pearls of wisdom.

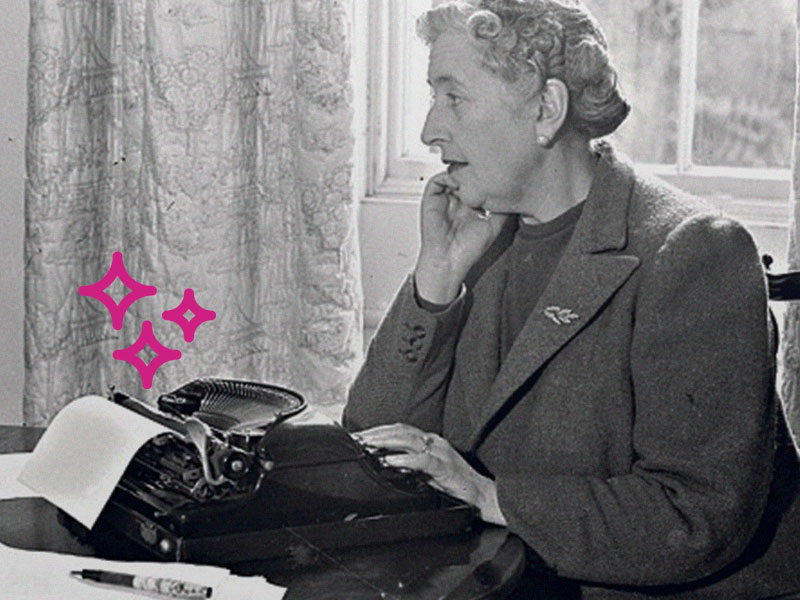

Agatha Christie

“The secret of getting ahead is getting started.”

The best writers are the most persistent, and Dame Agatha Christie was no exception. She wrote 85 books in her lifetime and her maximum estimated sales is currently 4 billion.

It may surprise you that it took several years for her to get ahead. Her first novel took four years to write, and many publishers rejected her before one took a chance.

For someone as prolific as Christie, you’d be forgiven for thinking writing came to her as naturally as breathing. But, she struggled just like everyone else. She said of writing, “There is no agony like it. You sit in a room, biting pencils, looking at a typewriter, walking about, or casting yourself down on a sofa, feeling you want to cry your head off.”

Frustration is all part of the package. Think of Agatha Christie next time you get the blank-page syndrome. To get ahead, you simply need to get started. Write something down, even if you don’t think it’s good.

Danielle Steel

“You’re better off pushing through and ending up with 30 dead pages you can correct later than just sitting there with nothing.”

Her novels may be formulaic, but her formula clearly works. She’s been a consistently bestselling author, and so far has written 179 books. In fact, she’s the bestselling author alive. Her maximum estimated sales currently stands at 800 million.

Her work ethic is a significant factor in her success. She expressed her bewilderment about “burnout culture” in her interview with Glamour Magazine. She spent her twenties holding a day job and writing after work and she clearly credits her success to “pushing on”. But, she concedes that she works a little too hard and wishes she’d had a little more fun.

You don’t have to work yourself into exhaustion, but you can still take some advice from this powerhouse. It’s better to write something you need to edit later than to have too much self-doubt, and no writing to show for your analysis paralysis.

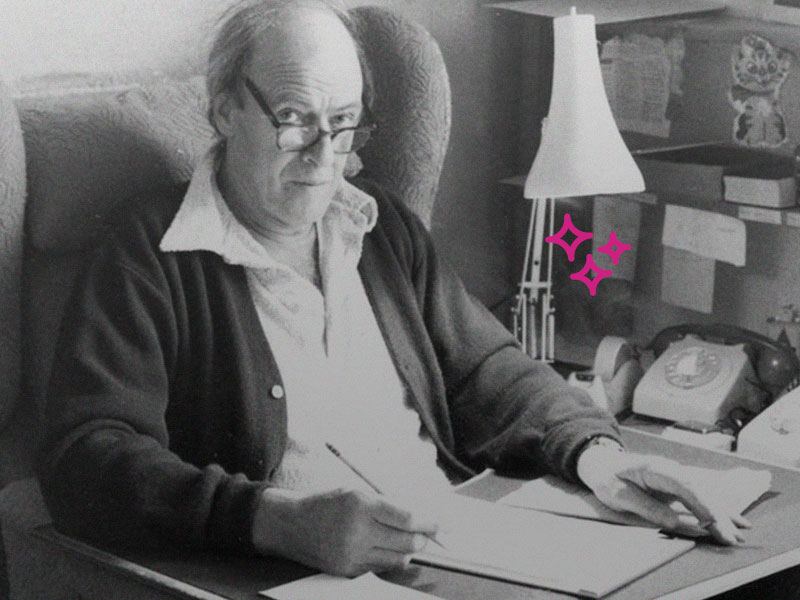

Roald Dahl

“You must be a perfectionist. That means you must never be satisfied with what you have written until you have rewritten it again and again, making it as good as you possibly can.”

Roald Dahl, although also a writer of books for adults, was a master of children’s literature. He wrote 50 books and his current maximum estimated sales is 250 million.

For Dahl, writing is one part of a scrupulous process. He emphasises the importance of editing your work. It might go through one redraft, or it might be countless until you’re satisfied.

The lesson to take away from Dahl is that it’s invaluable to have an effective editing strategy.

Corín Tellado

“I have sacrificed my life to literature. I hurt myself. But I’ll stop writing when my head falls on the typewriter. I do not give up.”

Prolific Spanish writer Corín Tellado is another lesson in sheer commitment. She wrote no less than 4,000 books and her maximum estimated sales is currently 400 million. Her work has been translated into several languages.

Unlike Danielle Steel, Tellado could not include eroticism in her novels. This was due to the strict censorship of the Spanish regime. She used this as a learning opportunity, saying of this struggle:

“There were months when up to 4 novels were rejected. Some novels were so underlined that there was hardly any letter left in black. They taught me to hint, to suggest rather than show.”

Instead of giving up, she used her struggle with censorship as a way to learn how to insinuate. The success she found is evidence that as writers, we can overcome obstacles if we just keep going. The workaround Tellado found for censorship may have made her writing even more effective than what she originally wanted to write.

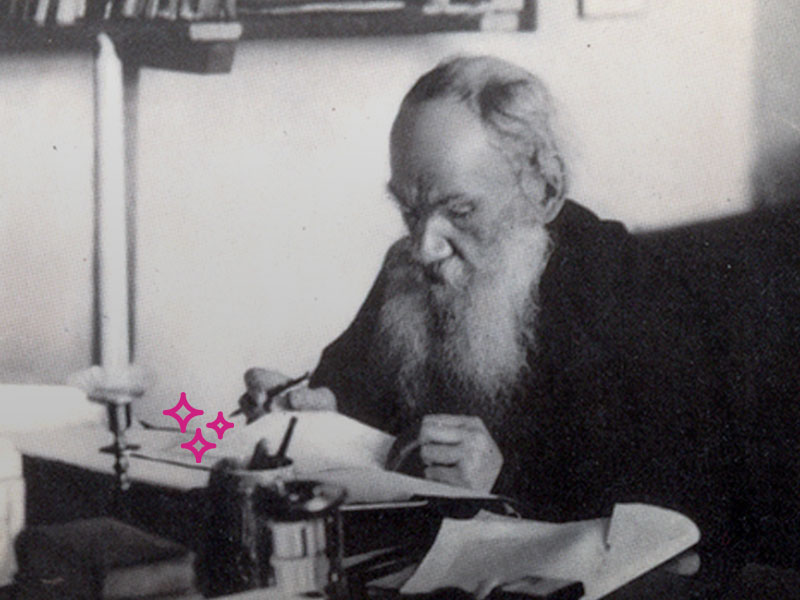

Leo Tolstoy

“In the name of God, stop a moment, cease your work, look around you.”

The Russian writer Leo Tolstoy is considered one of the greatest writers of all time. He wrote 48 books and his maximum estimated sales is 413 million. His books are considered the very best in Realism, so it’s fitting that the quote we used emphasises looking at the world around you.

The Realist movement aimed to use literature as a mirror for the world, depicting everyday experiences. It avoided artificiality and implausible elements in a story.

His advice here is a good reminder that we can get our heads stuck too deeply into what we’re writing. We forget the world around us – and, sometimes, the audience we’re writing for. It’s important to take a step back. Take a break from writing and try to be receptive to the world and the people around you. You might overhear an interesting conversation, or see something as small as a subtle facial expression, that will inspire you.

We hope these authors’ quotes inspired you, too.